Even with extremely noisy data, the system does not trigger at a threshold level set at one (1). Therefore, during normal operation, with no threats present, the process deviation should not be large enough to produce a trigger signal less than one (1) in this case.

However when the data for a cyanide incursion at 1 percent of the LD-50 or approximately 2.8 mg/L is superimposed on the system, the trigger level of 1 is easily exceeded (see Figure 4). Other contaminants exhibit similar results.

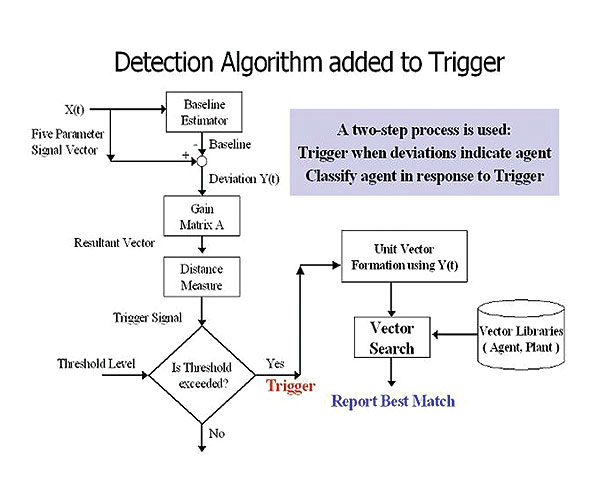

The deviation vector that is derived from the trigger algorithm contains significantly more data than what is needed to simply trigger the system. The deviation vector’s magnitude relates to concentration and trigger signal, while the deviation vector direction relates to the agent characteristics. Seeing that this is the case, laboratory agent data can be used to build a threat agent library of deviation vectors. A deviation vector from the water monitor can be compared to agent vectors in the threat agent library to see if there is a match within a tolerance. This system can be used to classify what agent is present (see Figure 5). Each vector results in a vector angle in n-space that, from the research conducted so far, appears to be unique to the class of agent present. The fact that the direction of the vector is unique for a given agent type allows the use of an algorithm to classify the cause of a trigger being set off. When the event trigger is set off, the library search begins. The agent library is given priority and is searched first. If a match is made, the agent is identified. If no match is found, the plant library is then searched and the event is identified if it matches one of the vectors in the plant library. If no match is found, the data is saved and the operator can enter an ID when one is determined. The agent library is provided with the system, and the plant library is learned on site.

The unknown alarm rate when the system is tracking real world data is also quite low. The system is equipped with a learning algorithm, so that as unknown alarm events occur over time, the system has the ability to store the signature that is generated during the event. The operator can then go into the program and identify that function and associate it with a known cause such as the turning on of a pump or the switching of water sources, etc. Then, the next time that event occurs; it will be recognized and identified appropriately.

Over time as the system learns, the probability of an unknown alarm that has not been previously encountered and identified will continue to decrease and will eventually approach zero. The probability of an unknown alarm due to a given event depends upon the frequency of the occurrence of such an event and the time that the algorithm has had to learn that event. Events that occur frequently will be quickly learned while rare or singular events will take longer to be learned and stored. This should result in a fairly rapid drop off in the number of unknown alarms as common events are quickly learned.

A number of similar multi-parameter measurement platforms, most without the addition of intelligent algorithms, have been evaluated for such applications by the EPA Environmental Technology Verification (ETV) program. See the full reports at http://www.epa.gov/etv/verifications/vcenter1-35.html. These systems appear to be a good choice for detecting water quality excursions that could be linked to water security events. There are a number of advantages to using such systems. The chief advantage is that these instruments are not new. They are common everyday parameters with which the average industry worker is quite familiar, thus adding a degree of comfort in operations not afforded by other new technology. As existing technologies, these instruments have been proven to be robust and dependable in prior field deployments. They represent measurements that would be of interest and use to water utility personnel and food industry process control engineers above and beyond their role as water security devices.

Process Improvement Capabilities

Through many years of experience, the best old hands at plant operations have developed “a sense” for knowing something in the system is amiss. It can be a smell, color, clarity (or lack there of), sound or just tingling in the nape of the neck. One gains these senses only by extensive experience in a particular facility. Due to the shrinking workforce and the loss of institutional knowledge at many facilities, bulk parameter monitoring in the distribution system with interpretive algorithms has the potential to become the artificial “sense” able to quickly “learn” the quirks of the distribution system and have those quirks labeled by those with extensive experience so that less experienced employees have the benefit of that knowledge without having to wait five, 10 or more years. A good phrase to describe this knowledge base would be “institutional intuition.” (Englehardt, 2005: Kroll, 2006).

ACCESS THE FULL VERSION OF THIS ARTICLE

To view this article and gain unlimited access to premium content on the FQ&S website, register for your FREE account. Build your profile and create a personalized experience today! Sign up is easy!

GET STARTED

Already have an account? LOGIN